Welcome To The Capitol

You can download a PDF version of this book here.

1. The Capitol

a. Welcome to The Capitol

b. Building and Rebuilding

c. January Sixth

d. The Capitol Today

e. Did You Know?

2. The U.S. Capitol Visitor Center

a. Welcome to the Capitol Visitor Center

b. Facts and Facilities

c. Education and Exploration

d. When You Visit

i. A Great Experiment

ii. No Guarantees

iii. People Like Yourself

e. Did You Know

3. The Capitol’s Architecture

a. Welcome to the Capitol’s Architecture

b. Architect of the Capitol

c. Work Begins

d. Revision and Expansion

i. Criticism

ii. Conflict

iii. Mixed Stylles

iv. New Uses

v. Economy Versus Permanence and Beauty

e. Conclusion

f. Did You Know?

4. The Rotunda

a. Welcome to the Rotunda

b. A Space of Many Uses

c. Inspire, Memorialize, Share

i. The Apotheosis

ii. The Frieze

iii. The Eight Paintings

iv. The Statues

v. Sandstone Carvings

d. Did You Know?

5. National Statuary Hall

a. Welcome to National Statuary Hall

b. History

c. Key Features

d. Artwork

e. Other Uses

f. Did You Know?

6. The Senate Chamber

a. Welcome to the Senate Chamber

b. The First Two Senate Chambers in the Capitol

c. The Current Chamber

d. Senate Desks

e. Did You Know?

7. The House Chamber

a. Welcome to the House Chamber

b. Evolution of a Meeting Space

c. Musical Chairs – And Desks

d. Inside the Chamber

i. The Mace

ii. Portraits

iii. Inkstand

e. Watching Democracy at Work

f. Did You Know?

8. The House Wing

a. Welcome to the House Wing

b. The Hall of Columns

c. Minton Tiles

d. The Iron Library

e. Bronze Doors

f. Did You Know?

9. The Senate Wing

a. Welcome to the Senate Wing

b. Electric Lightings

c. The Brumidi Corridors and Meeting Rooms

d. The President’s Room and the Vice President’s Ceremonial Office

e. Did You Know?

10. The Crypt

a. Welcome to the Crypt

b. A Changing Space

c. Honoring Washington

d. Today

e. Did You Know?

11. The Capitol Grounds

a. Welcome to the Capitol Grounds

b. Three Hands

i. L’Enfant

ii. Olmstead

iii. White

c. Treasures

i. The Summerhouse

ii. Court of Neptune Fountain

iii. Taft Memorial and Carillion

iv. Trees

v. Ulysses S. Grant Memorial

vi. Senate Parks and Fountain

d. Conclusion

e. Did You Know?

12. Capitol Hill

a. Welcome to Capitol Hill

b. Architect of the Capitol

c. The Library of Congress

d. The Supreme Court

e. The Botanic Garden

f. Capitol Tunnels

g. Part of Capitol Hill is no Longer on Capitol Hill

h. Did You Know?

13. Learn More

Notes

Legal

Images

Intent

Chapter 1

The Capitol

The words capital and capitol can easily be confused. Though pronounced the same, capital (with an "a") refers to the city where a county's central government is located. It is also the topmost, scroll-like portion of an architectural column. The Capitol (with an "o") is the name of the building where Congress meets –and the name of a temple in Rome. So, you could say: The capitals atop the columns of The Capitol (spelled with a capital "C"), and modeled on The Capitol in Rome, can all be found in the nation's capital.

The Capitol and the Summerhouse in the spring

Welcome to The Capitol

The U.S. Capitol has evolved over time in its use, its design, and most notably in its size. However, it's most important purpose has remained constant throughout its 200+ year history; namely, as the home of the first branch of our government – the Legislature. Following the one sentence preamble or introduction of The Constitution, the very first subject addressed in Article I, Section 1 is the establishment of Congress. And shortly thereafter, The Constitution provides for the creation of a federal district to become "the Seat of the Government of the United States."

Where that federal district should be located was left unsaid and it was up to then-President George Washington to select the land now known as the District of Columbia or Washington, DC. The District was originally a square, ten miles per side, oriented so its corners pointed due north, south, east, and west. With some of that original land returned to Virginia, the District now comprises just over 68 square miles instead of the original 100. Pierre Charles L'Enfant, a French engineer, was engaged to design a detailed plan for the new city. Influenced by European cities like Paris, L'Enfant laid out a strict grid pattern for the city's streets, intersected by broad avenues running on diagonals. This resulted in a number of smaller, triangular-shaped parcels of land, which were perfect for parks and welcomed green space.

But the question remained: Where to situate a building for the nation's new legislature? After surveying the land, L'Enfant selected Jenkins' Hill, the second-tallest point in the city for the new Capitol building. Over time the area came to be known as Capitol Hill or simply The Hill. L'Enfant's sense of symmetry and proportion might have led him to place The Capitol at the direct center of the city, but with Jenkins' Hill rising 88' above the nearby Potomac River, the site's elevated prominence made it a natural choice. Here would rise the permanent home of Congress, which would meet in eight other cities before moving to Washington; Philadelphia, Baltimore, Lancaster, York, Princeton, Annapolis, Trenton, and New York City.

As visitors to the city soon discover, Washington, DC is divided into four quadrants (Northwest, Northeast, Southwest, and Southeast), with numbered streets running north-south and first lettered and then syllabled streets running east-west. All of the streets radiate from a central point with the numbering and naming beginning anew in each quadrant. That means there are, for example, actually four intersections of 4th and D Streets, but each with a separate quadrant designation (NW, NE, SW, SE).

And where is that central point where all of the quadrants meet? At the exact center of The Capitol there is a marble compass rose embedded in the floor of the Crypt, the room originally intended as the burial place for George Washington. L'Enfant chose The Capitol as the city's center to underscore the importance of Congress.

Building and Rebuilding

In addition to his plan for the federal city, L'Enfant was to have designed the new Capitol. However, when he failed to produce the drawings, the nation's first Secretary of State, Thomas Jefferson, instead held an architectural competition. The winner was to receive $500 and a plot of land in the city. None of the plans submitted though pleased President Washington.

Fortunately, Dr. William Thornton, a Scottish physician and amateur architect, living in the British West Indies, asked to submit a design. And even though the competition was then closed, he was invited to present. His plan pleased both the three Commissioners overseeing the District and the President, who gave it his approval on July 25, 1793. Less than two months later, on September 18th, Washington laid the cornerstone at what was to be the southeast corner of the building.

Thornton's original plan for The Capitol

Congress imposed a seven-year deadline for completing and occupying The Capitol, but with inadequate funding and difficult working conditions (all of the stones had be quarried and then ferried up-river some 40 miles), the project fell behind schedule. It was decided to concentrate all efforts on what is today the Senate side of The Capitol and by 1800 that portion was sufficiently completed to accommodate the House, the Senate, the Library of Congress, the Supreme Court, and the courts of the District of Columbia.

Seven years later, the House of Representatives moved into its wing, which was itself completed four years after that. By 1811 the two wings were connected only by a covered, wooden walkway.

On August 24, 1814, during the War of 1812, the British set fire to The Capitol. It did great damage to the buildings, which were saved only and fortunately by a heavy rainstorm. Damage from the fire and weathering of the original sandstone meant years of reconstruction, this time using marble brought all the way from Massachusetts. A copper-covered wooden dome was added to the central space. But by that time, with the increasing number of states and the increase in overall population, the meeting places of both the House and the Senate had grown cramped. New chambers were built, with the House of Representatives occupying its own in 1857 and the Senate theirs two years later. The House's old chamber came Statuary Hall and the Senate's previous home became the Supreme Court from 1860-1935 and was then restored to replicate the old Senate chamber for visitors.

Work was again suspended during the Civil War, during which The Capitol was used as a military barracks, a hospital, and even a bakery. With the then greatly expanded north and south wings in place, it was apparent that the dome was now too small and out of proportion to the rest of the building. By 1863 a new cast iron and masonry dome was in place and the stunning 19' 6" statue of freedom secured at its peak, giving the profile we know today.

Meanwhile, Frederick Law Olmstead, a leading landscape architect, famous for designing New York City's Central Park, created a sweeping and graceful plan for the surrounding grounds and walkways, most of which can be seen and enjoyed today. An underappreciated aspect of Olmstead's design was the way every element, whether tree grove or fountain, lantern or path, all work to preserve views of The Capitol and enhance its preeminent position atop Capitol Hill.

Over the following years, expansions and restorations continued, prompted in part by a fire and gas explosion. Most notably, the east front (the long side facing the Library of Congress and the Supreme Court) was faithfully reproduced in marble and moved more than 32' outward, creating additional meeting and office space. The west front (facing down the National Mall toward the Lincoln Memorial) was also restored, replacing the original sandstone with more durable limestone. Both sides received substantial stairs and terracing, giving the building a more solid and grounded appearance. And one by one, modern conveniences were added as well, including steam heat, elevators, electric lighting, air conditioning, fireproofing, and more.

By far the largest addition to The Capitol was completed in 2008, the adjoining Capitol Visitor Center, located underground, beneath the east plaza. The Center (or CVC) is larger than 10 football fields and now welcomes millions of visitors from around the world each year. It is the starting point for Capitol tours and houses a theater and dozens of exhibits. L'Enfant had originally called Jenkins' Hill "a pedestal waiting for a superstructure." Given The Capitol's size and grand proportions today, L'Enfant would surely have been pleased. Much like the history of the republic is symbolizes, The Capitol has continued to evolve and improve over time, reflecting both the needs and the aspirations of the nation's citizens. It has rightly been called The People's House, keeping safe some of our greatest treasures and providing the backdrop for our most ambitious futures.

January Sixth

West front of The Capitol, January 6, 2021

Having described elsewhere the damages inflicted on The Capitol by multiple fires, construction collapse, the War of 1812, and its use as a bakery and a barracks during the Civil War, it would be remiss not to mention the damages The Capitol sustained on January 6, 2021. The political and social damages perpetrated that day are beyond the scope of this book. Suffice it to say that they continue to this day and their outcome is less than certain.

First and foremost, we should not forget those who died directly and indirectly as a result of the riot.

The Capitol itself sustained a minimum of $30 million in damages. Doors, windows, paintings, sculptures, murals, historic furniture, two of the Olmsted lanterns, and even the Columbus Doors on the east front of The Capitol were all damaged, defaced, or destroyed. Furniture, laptops, and more were stolen. Damage from pepper spray, bear repellant, fire extinguishers, blood, and feces was extensive. A full restoration of the building, the grounds, and the artifacts will take years to complete.

The Capitol Today

Today The Capitol itself is one of 15 nearby buildings overseen by Congress, including nine office buildings, the U.S. Botanic Garden, The Capitol Visitor Center, three buildings housing the Library of Congress, and the Supreme Court. The U.S. Supreme Court is generally considered part of The Capitol complex and even though it is overseen and maintained by the Architect of The Capitol, it is actually the seat of the separate, judicial branch of our government. Despite the priceless works of art it contains and the lofty allegorical symbols with which it is adorned, The Capitol is first and foremost a working office. Every day, people come to The Capitol to help conduct the nation's business. In addition to the 100 Senators and 435 Members of the House of Representatives, over 10,000 people work in The Capitol itself and the surrounding offices doing everything from constituent and legislative services to sorting mail, doing maintenance, serving meals, providing security, escorting and informing visitors, and so much more. This small city (with over half a dozen of its own Zip Codes!) is not just The Capitol…it is Your Capitol.

In the next chapters, we'll look more closely as some of The Capitol's special places and the important events that occurred there.

Did you Know?

1. Many people believe it is a law that no building in Washington, DC can be taller than The Capitol. That is a myth. The city's building height restriction, enacted in 1910, was motivated by fire safety and wanting to preserve the open character of the broad city streets.

2. And speaking of height, Capitol Hill is not the highest hill in DC. That honor goes to Reno Hill in Fort Reno Park in upper Northwest DC. Why do you think Reno Hill was not chosen as the site of The Capitol? Could it be its distance from the river? Why would that have been important?

3. Washington, DC is not the only U. S. city divided into quadrants. Albuquerque (NM), Rochester (NY), Miami (FL), and Atlanta (GA) also have four quadrants.

4. L'Enfant's original name for the federal district was Washingtonopolis. (Polis is a Greek word meaning city.)

5. The Tholos, or lantern, the windowed area directly beneath the Statue of Freedom atop The Capitol dome, is lit whenever either the House or the Senate is in session or to mark a special occasion.

6. After much research and actual digging, we think we know where The Capitol's cornerstone is located, but we have no proof. It's roughly 5' x 3' x 1' and part of the southeast corner of the building's foundation, pointing generally to where the Cannon Office Building sits today.

Chapter 2

The U.S. Capitol Visitor Center

Welcome to the U.S. Capitol Visitor Center

Located below-ground and immediately to the east of The Capitol, the U.S. Capitol Visitor Center is the newest addition to Capitol Hill and the starting point for all Capitol tours. It is not only your entry to The Capitol and your introduction to Congress, but it is also an engaging presentation of the country's founding, principles, and most interesting contributors to its success.

Built over the seven-year period from 2002-2008, the U.S. Capitol Visitor Center (CVC) was conceived to meet a host of visitor needs. Prior to its opening, many of the millions who came each year to tour The Capitol found themselves waiting in long lines outdoors, no matter what the weather. And even after that long wait, many had to be turned away because there was no capacity to safety bring such large numbers of people through the Rotunda, Statuary Hall, the Crypt, and more. Nor were there adequate restaurant and restroom facilities available. And disappointing to many, the old approach of queuing and touring gave little opportunity to understand the history of the building and the backgrounds of the people who built The Capitol and who worked there to perfect the union this building symbolizes.

Facts and Facilities

The CVS is large. It covers 580,000 square feet over three levels, and is roughly threequarters the size of The Capitol itself. It was built below ground level so that The Capitol would remain the central focus of The Hill, just as Capital planner Pierre L'Enfant had intended when selecting Jenkins' Hill as its location and as landscape planner Frederick Law Olmstead had intended when designing the surround grounds. In fact, in building the CVC, a large and unattractive asphalt parking area was removed from the east front area and the graceful lines of Olmstead's vision were restored. 60 trees that had to be removed were replaced by 85 new trees.

For visitors' convenience, there are two coat checks, a large restaurant, two information desks, and eight restrooms. The entire CVC is wheelchair accessible, and wheelchairs are available at the coat check areas. Listening devices are available with different language versions of the tour as are devices with audio descriptions for the hearing impaired.

Education and Exploration

Exhibition Hall

Any Capitol experience begins in The Capitol Visitor Center's Emancipation Hall. There, two immense (30' x 70') skylights offer stunning views of The Capitol dome overhead. The Hall's name dates to a 2007 act of Congress, meant to honor the enslaved persons who helped build The Capitol. Two bronze busts pay tribute to those laborers as well as the nation's commitment to all oppressed people; Sojourner Truth, an escaped slave who became a well-known abolitionist and promoter of women's rights, and Raoul Wallenberg, a Swedish diplomat credited with saving the lives of tens of thousands of Jews during World War II.

Guided, 45-minute tours of The Capitol begin at the CVC. There you'll be shown a brief orientation film, Out of Many, One, describing the purpose, uses, and history of The Capitol and how it was built, destroyed, rebuilt, and now maintained over its more than 200-year history. The tour will then bring you through the Crypt, the Rotunda, and National Statuary Hall, all described elsewhere in this book.

Either before or after your tour, you may want to do some exploring. 18 statues are placed around Emancipation Hall and the CVC's upper level. These are part of the state-donated collection, whose other statues appear in the Rotunda, the Crypt, and of course Statuary Hall.

Dominating this space, however, is the full-sized plaster model of Thomas Crawford's statue of Freedom that stands atop The Capitol dome. Like its bonze counterpart, it is over 19 feet tall. You'll be able to see some of the remarkable details, like the eagle helmet, that are difficult to discern when standing outside and looking up nearly the length of a football field. The model itself has an interesting history, having years ago been sawn into pieces and stored in different locations until being brought to the CVC and reassembled. At the time, the model was covered in lead paint, all carefully removed by hand. And, in a wonderful reversal, restorers knew exactly how to repair the damaged plaster because some of them had been the very people who had years before restored the bronze original far above.

One man who worked on the casting of the statue, Philip Reid, was a slave, purchased by the Foundry owner, Clark Mills. As was the custom at the time, Reid worked throughout the week and was paid only for his labor on Sunday, all other salary going to Reid's owner. Reid became a free man in 1862, when President Lincoln signed the Compensated Emancipation Act, though it is not known if Reid was present for the completion of the installation atop the dome a year later.

Immediately behind Freedom is Exhibition Hall, with its many models of The Capitol throughout the years, historic documents, and many artifacts. A large hands-on scale model of the dome and central section of The Capitol gives visitors a sense of the intricate detail of the dome and the proportions that give it monumentality and grace.

The six principal exhibit spaces are each keyed to different times, stretching from the very first Congress to the present day. Together, they constitute a timeline of essential American history, giving context to the building of a nation, not just the building of its halls of government.

When You Visit

There is so much to see and so much to learn when you visit the CVC and tour The Capitol, as many millions have done since the CVC opened its doors on December 2, 2008. Sometimes it can be a bit overwhelming! Here are three thoughts you might keep in mind when you visit that may help you connect everything you experience there.

Alexis de Tocqueville

• A Great Experiment

In the early 19th Century, French diplomat and historian Alexis de Tocqueville visited the United States and wrote a remarkable two-volume memoir, Democracy in America. Praised for his insight into the American character and the functioning of our government, Tocqueville referred to America as a "great experiment." As you read the documents and listen to the words of various Founders, Presidents, and Members of Congress, you'll see that this description still applies. Our history really is an ongoing experiment as we continually try to perfect a government that protects, serves, and respects all of its citizens. Continually building a better America is a long and fascinating process, as important today as it was in 1776.

• No Guarantee

It's easy to think that the form of government we have, the freedoms we enjoy, and even the prosperity we experience are somehow natural and to be expected. As you learn about the many challenges America has faced, you'll see that there has never been a guarantee of our success. The debates in the Continental Congress could have shaped our future in profoundly different ways. The wars we fought for independence, for union, and for democratic values could have turned out quite differently. Times of fear and uncertainty could easily have curtailed freedoms and blunted our liberties. Our only assurance that the American experiment will succeed is, and has always been, our own hard work and persistent vision.

• People Like Yourself

The marble columns and gilded ceilings of The Capitol are unique and beautiful national treasures. The words and ideas contained in documents like The Declaration, The Constitution, Lincoln's Inaugural, and so much more are eloquent and inspiring. But it has always been the sacrifice and courage of individuals, of people much like you, who contributed to making America better in every way. As you look at the statues in the CVC, the Rotunda, Statuary Hall, the Crypt, and elsewhere, think about the lives of the people they represent. They were farmers, reporters, explorers, preachers, teachers, lawyers, merchants, an actor, astronaut, biologist, artist, blacksmith, engineer, and even a keen-eyed humorist and a young girl who overcame blindness, deafness, and the inability to speak.

The American people are our greatest treasure and have made the country we know today. So, what contribution will you make?

Did You Know?

1. Construction of The Capitol Visitor Center required the removal of 65,000 truckloads of soil.

2. The Center hosts some three million visitors each year; 15,000-20,000 a day during peak season. In its first ten years of operation, the Center saw 21 million visitors.

3. Unlike most construction, which starts with a foundation and then builds upward, the CVC was built top-down (with its roof at ground level) to ensure the space above ground was accessible in time for the inauguration of 2005.

4. An underground tunnel allows people to move easily between the Capitol Visitor Center and the Library of Congress.

5. Though the CVC and The Capitol are sited on what L’Enfant called Jenkins’ Hill, Thomas Jenkins was in fact not the owner of the land. Daniel Carroll leased the land to Jenkins for grazing, and it was Carroll who conveyed the land to the federal government, not Jenkins.

Chapter 3

The Capitol's Architecture

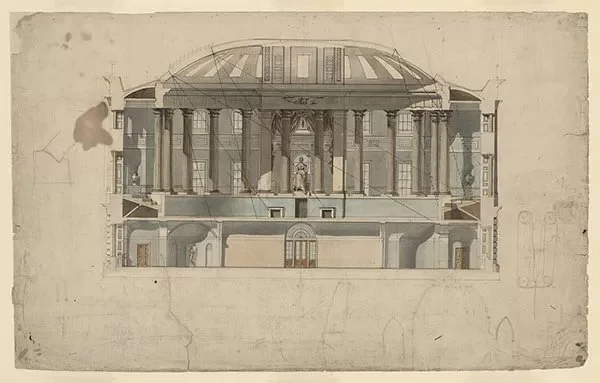

Latrobe’s drawing of the House Chamber

Welcome to the Capitol’s Architecture

From paintings to statues, and even picture frames and clocks –nearly every object in The Capitol has a symbolic meaning. The bundled fasces represent strength from unity and the original 13 colonies. Snakes depict wisdom while eagles remind us of strength and soaring independence. The Latin inscriptions draw a line back to some of the earliest examples of republican government. The statues and paintings illustrate leadership, courage, sacrifice, devotion, and contribution. These reminders of our history, our values, our strengths, and our heroes are ever-present and impress upon legislators and visitors alike our shared heritage and common purpose.

But the building itself is also a symbol. In fact, it is many symbols. The Greek and Roman architectural elements are not merely decorative; they are evocative of the earliest democracies in Greek city-states, of elected leadership in the Roman senate. Bedrock principles of American government are recalled simply by looking at the building that Houses our legislature. And, yes, there is beautiful, white, Italian marble in The Capitol, but there is also sandstone from Virginia; granite from Texas, Maine, Massachusetts, and Virginia; and marble from Georgia, Vermont, Virginia, Pennsylvania, New York, Massachusetts, Maryland, and Tennessee –all as befits a nation of such vast and varied resources. Such use of native materials was certainly informed by economy, but for that, their quality and beauty can not be denied and there is justified pride in using stone hewn within our own borders.

Though it may be hard to imagine now, there was no guarantee that the young nation would survive, let alone flourish and thrive. So architecture was also used as a way of embodying permanence and substance. And it reflected our continual expansion and growing self-assurance.

For all of that, one may wonder why a nation striking out in such radically new directions should, really without question or pause, from the beginning wish to build its Capitol in the very same styles so predominant in Great Britain and throughout Europe. It was because these styles were not thought of as European or continental but simply as the highest expression of the architectural and building arts. Columns, capitals, entablatures, and pediments were only Doric, Tuscan, Ionic, Corinthian, or composite. Period. Each of these styles, or orders as they are called, was strictly defined by ratios, measures, and rules that made them recognizable and meaningful to the architects and builders of The Capitol. With time and growing confidence, architects of The Capitol defined new "orders," which were proudly and unmistakably American. For example, Benjamin Henry Latrobe, the second architect of The Capitol, designed capitals depicting corncobs (East Vestibule) and others representing tobacco leaves (Small Senate Rotunda), both native species that were critical to the early nation's economy.

Architect of The Capitol

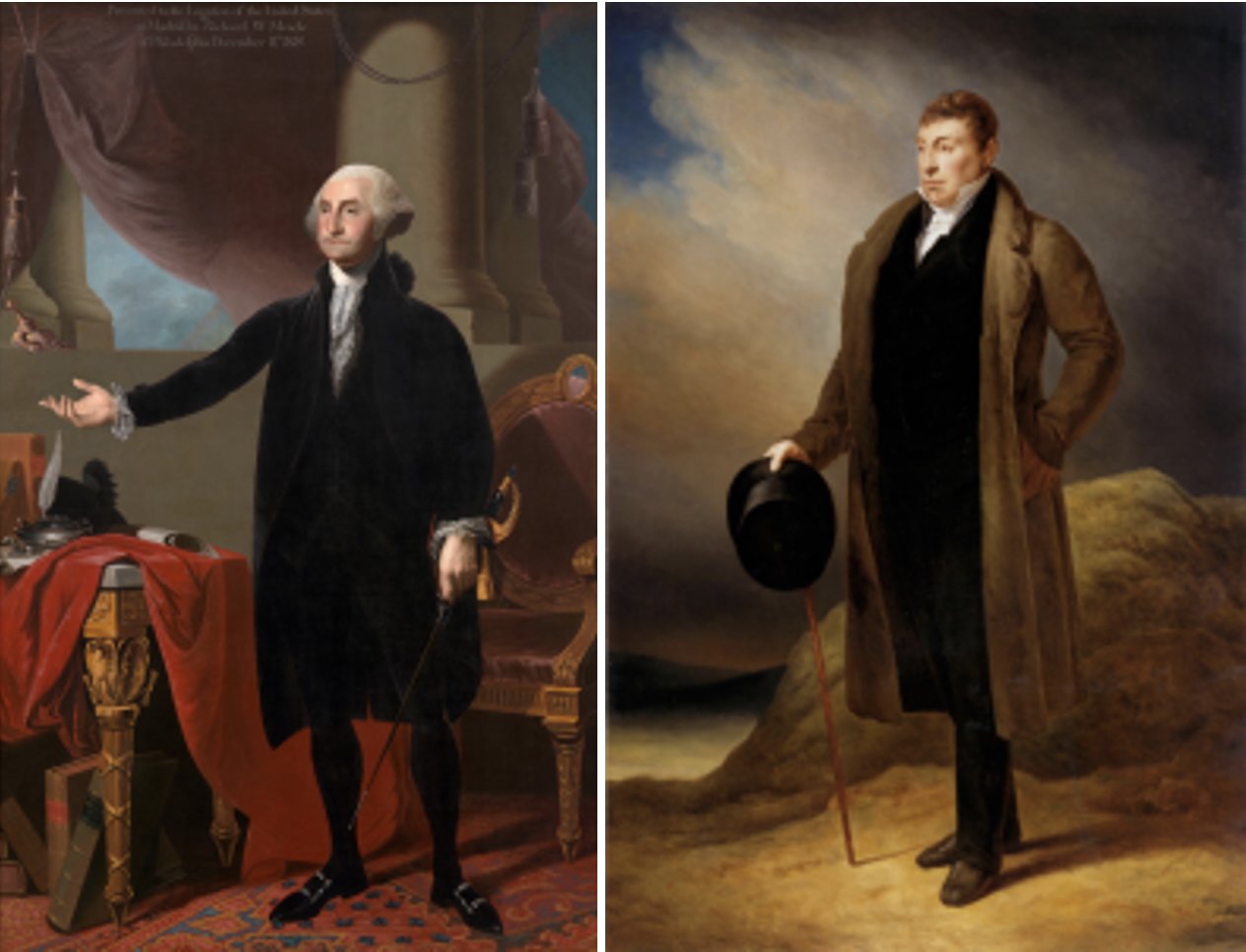

Dr. William Thornton – First Architect of The Capitol

The word architect comes from two Greek words meaning chief builder. While today we might think of architects more as chief designers, throughout much of The Capitol's history, chief builder was a more accurate description. That highlights –and perhaps explains– a good deal of the conflict between on the one hand the architects of The Capitol and on the other hand the commissioners who oversaw the architects and the construction foremen who oversaw the workers. The distinctions between these roles were never very clearly drawn and often very clearly disrespected. Nor did these people all have an equal and deep knowledge of engineering, of materials, of finance, of the power of visual symbols, or even of the importance of stylistic integrity. And, to make the story even more interesting, we can add Presidents and Members of Congress to the collection of people contending over one aspect or another of the building of the U. S. Capitol.

Which makes it all the more remarkable, when you look at The Capitol today, to see a building and its surrounding grounds that are beautiful, inspiring, and harmoniously composed. And remember, too, that there was never just one plan for The Capitol, and all that was needed was to carry its construction through to completion. On the contrary, there were many different designs for different portions of The Capitol, there were fires and wars that destroyed it, there were materials and construction that needed to be replaced, and there were as well multiple repurposings of the spaces themselves. How it all worked out is an engrossing story. How it functions today as both a monument and a workplace is truly extraordinary.

To date there have been 13 architects of The Capitol, though not all have shared that exact title. Some of them, like Benjamin Latrobe and Charles Bulfinch, will be mentioned in following chapters, but all faced significant challenges and all but a few finished their tenure with mixed feelings; proud of what they had achieved but exhausted by the effort it took to do so. Two other persons are worthy of mention here as well. Pierre L'Enfant was the engineer appointed by George Washington to survey the land that was to become Washington, DC; design its streets, parks, and broad avenues; and select the site of The Capitol, White House, and more. The other was Frederick Law Olmstead, the landscape architect responsible for the graceful layout of walkways and green spaces that define Capitol Hill as a harmonious whole. More about both of these later. Taken together, the efforts of all of these men have given us The Capitol we admire and given the world the symbol it respects.

Work Begins

Cox Corridor painting of George Washington laying The Capitol’s cornerstone

Following the passage of the Residence Act in 1790, declaring the general location of the new federal district, President George Washington appointed Pierre L'Enfant to survey the land and devise a plan for the new city. The following year, Washington appointed a three-member Board of Commissioners to oversee the city's administration –and L'Enfant. None of the three had any background or education in architecture or engineering. In contrast, L'Enfant was an engineer who had attended the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in Paris.

L'Enfant proceeded to lay out the city, as directed, selecting Jenkins' Hill for the site of The Capitol. However, he repeatedly failed to provide required designs for The Capitol building or the White House. In fact, he refused to provide his four-quadrant, grid-and-axel design of the city, forcing brothers and associates Andrew and Benjamin Ellicott to redraw the plan from memory. As a result, L'Enfant was dismissed in 1792.

With two years lost on The Capitol and the 1800 deadline for its occupancy moving ever nearer, Jefferson suggested a design competition. The announcement detailed a few requirements, for meeting and committee rooms and such, but no specific style. Jefferson was an ardent classicist, based on his time in Paris, where he particularly admired the Parthenon, and his study of Andrea Palladio and other early designers. Both his design for the University of Virginia and that for his own home (Monticello) expressed this clear preference. Of the design for the new Capitol, he wished it to be based on “one of the models of antiquity, which have had the approbation of thousands of years.”

At least 18 designs by 10 men were received by the deadline. Only one entrant, Etienne (Stephen) Sulpice Hallet, was an architect, and both Washington and Jefferson saw enough promise in Hallet's design to request several rounds of revisions. But a late entry by Dr. William Thornton was accepted and awarded the competition prize, and the Commissioners, perhaps wanting to compensate Hallet, then asked him to review and criticize Thornton's plan, setting an unfortunate precedent. In the end, the design became a forced marriage of Thornton's exterior (a Georgian building with Corinthian columns) and Hallet's interior. This was the origin of the 2nd floor becoming the building's main floor (a “radical and incurable fault" –Latrobe), a situation that would not be elegantly resolved until the addition of porticoes and grand staircases, as well as the central Rotunda, all many years later.

Nonetheless, work began in July of 1793 and the cornerstone was laid with great ceremony by President Washington in September of that year.

Revision and Expansion

Construction of the new Dome in 1859

Work on The Capitol proceeded apace and Congress and the Supreme Court took up residence in the new building, as planned, in 1800. However, not as planned, only the North wing had been built out and even that was not fully completed. By 1802 the Commission was disbanded and then President Jefferson appointed Thomas Munroe to be the city's administrator. One year later, Jefferson invited Benjamin Latrobe to become “surveyor of the public buildings,” and new commissioners were installed. Latrobe's tenure was remarkable not only for his designs but because it encapsulated and illustrated trends that would continue in one form or another for the next 200 years.

• Criticism

Just as Hallet had found Thornton's design wanting, Thornton criticized Latrobe, Latrobe faulted Hallet, Bulfinch found fault with Latrobe's work, and so on. Unfortunately, much of this was played out in public and no doubt distracted from the work at hand.

• Conflict

John Lenthall, the "Clerk of the Works" or construction foreman for Latrobe, often substituted his judgment for Latrobe's expertise, changing materials (e.g., timbers rather than brick for arches) and designs at will. The commissioners were constantly requiring Latrobe to travel to evaluate and select new marble and making their own design changes. In much the same fashion, Architect Thomas U. Walter would later battle Montgomery C. Meigs, the "engineer in charge," over cost, design, and more.

• Mixed Styles

Reflecting multiple designs, changing tastes, and different uses of spaces, The Capitol contains nearly every classical architectural order, and yet remains a dignified and unified whole. Doric columns can be found in the Crypt and the Old Supreme Court Chamber, Ionic in the Old Senate Chamber, Corinthian in the Hall of Columns, the Small Senate Rotunda, the East Vestibule, and the east and west fronts. The composite order can be found there in the Old House Chamber, containing Jefferson-requested Corinthian columns topped by Latrobe-favored Roman entablature. And even the Tuscan order was present in the form of four Capitol gatehouses, two of which now survive in President's Park, about a mile and a half west on the National Mall.

• New Use

The House, Senate, and the Supreme Court have each occupied at least two different rooms within The Capitol itself, and additional spaces outside. As the number of states and the nation's population continued to grow, both the House and the Senate required more space in which to conduct their debates.

• Repairs

Between fires (1826 and 1851), wars, and natural deterioration, The Capitol has been in a near constant state of repair. By 1802, just two years after Congress took up residence in the new Capitol, Latrobe reported finding dry rot in supporting timbers, leaking roofs, and leaking skylights, among other problems. And Latrobe and his successors would deal with complaints about acoustics, lighting, and temperature, all of which arose from design decisions that they and their predecessors had made.

• Economy Versus Permanence and Beauty

The architects who designed The Capitol understandably wanted it built using the finest and most permanent materials available. In the original Senate chamber and The White House the preference was for marble columns, but they were deemed too expensive and were instead constructed of wood covered in plaster, supporting plaster, not carved stone, capitals. Even during World War II, when the ceiling of the Senate chamber was in danger of collapse, it was thought too expensive (or too unseemly during a time of war and privation) to repair it. In both instances, and many others, the better materials were eventually used and the repairs effected. Bringing The Capitol to its present state was a long and interrupted process. Even today, the Architect of The Capitol employs more than 2,400 people to preserve and maintain The Capitol in a pristine working state.

Conclusion

In the following chapters you'll see how these stories played out against the backdrop of America's rise to prominence and how The Capitol became a symbol of freedom and democracy admired around the world. You'll see how The Capitol's architecture expressed beliefs and chronicled struggles, and how, ultimately, it succeeded beyond any of the Founders' visions.

Did You Know?

1. At the time of The Capitol design competition, there were no domes atop public buildings in America. Most state capitol buildings had towers instead, like Independence Hall in Philadelphia. Jefferson's home (Monticello) was the first private residence in the country to have a dome.

2. A three-year restoration of The Capitol's dome and Rotunda was completed October 27, 2016. The cast-iron dome had over 1,000 cracks and significant rust and breakage. The entire structure was stripped of old paint and thoroughly repaired. It was then repainted, with three coats, using 1,215 gallons of paint and primer.

3. There is a full-sized replica of the U.S. Capitol in Wuhan, China. It was never completed and today houses a driving school.

4. In 1787, as bathing came into fashion, Carrera marble bathtubs were installed in The Capitol for Senators and tin tubs for Members of the House. Located on the basement (1st) level, the tin tubs have all been removed but one of the marble tubs remains.

5. To lend a sense of architectural continuity between the Visitor Center and The Capitol itself, the CVC’s walls are clad in sandstone, meant to evoke the walls of the Rotunda.

Chapter 4

The Rotunda

Welcome to the Rotunda

Like the Statue of Liberty and the Liberty Bell, The Capitol dome is recognized around the world as a symbol of America. But within that dome is an equally magnificent space, celebrating our history, declaring our values, and recognizing the contributions of important individuals. It is the U. S. Capitol Rotunda.

Soaring 18 stories tall, the Rotunda sits mid-way between the House and Senate Chambers and directly above the Crypt where George Washington was to have been buried. From side to side and floor to ceiling the Rotunda measures 96 feet across and just over 180 feet high. This vast and impressive space is open year-round and hosts more than 2 million visitors every year

The Rotunda as we see it now was begun in 1855, replacing an earlier and smaller structure. That first Rotunda was only about half as large, measuring 96' tall by 96' wide and shaped like half a sphere. It was made of copper and wood and designed to look like the Pantheon in Rome. It was lit by a single opening, an oculus or eye, at the very top. Over an 11-year period that spanned the Civil War, the dome was replaced with the cast iron structure we see today, and the Rotunda was rebuilt with sandstone, quarried some 40 miles south of Washington, DC. The oculus was replaced with 36 large windows, circling an upper section, and bathing the interior with natural light.

A Space of Many Uses

The Rotunda used as barracks during the Civil War

The Rotunda is a must-see stop on all Capitol tours and citizens from across the U. S. and visitors from around the world delight in its many artworks and grand displays. From time to time, Congress makes use of this special space for purposes both solemn and celebratory. Congress reserves its highest recognition for the nation's leaders by the ceremonial lying in state. The caskets of Presidents Lincoln, Kennedy, Eisenhower, Johnson, Reagan, Ford, and Carter, among others, were placed in the center of the Rotunda and watched over by a ceremonial military guard while the public was allowed pass by and pay its respects. Congress has similarly recognized the contributions of extraordinary citizens, such as Rosa Parks, allowing them to lie in honor in the Rotunda.

The Congressional Gold Medal is awarded by both the House and Senate jointly to those who have made extraordinary contributions to the country or humanity. It is the highest civilian recognition made by Congress, on a par with the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Traditionally the Gold Medal award ceremony is held in the Rotunda. Recipients have included explorers, inventors, civil rights pioneers, artists, sports figures, humanitarians, and others, from the U. S. and abroad, including the Wright brothers, Thomas Edison, Dr. and Mrs. King, Robert Frost, Winston Churchill, Marion Anderson, Nelson Mandela, Dorothy Height, Aung San Suu Kyi, and more than 180 others. And (posthumously) Constantino Brumidi –remember that name and keep reading!

The other uses Congress makes of the Rotunda is for unveiling new statues. Beginning in 1864, Congress asked each state to contribute two statues to The Capitol, each depicting someone with a special connection the state. Today, the 100 statues, the last being Johnny Cash from Arkansas, are dispersed throughout The Capitol complex, in Statuary Hall, the Crypt, the Capitol Visitor Center, and the Rotunda. Newly unveiled statues are typically left in the Rotunda for six months, then moved to another, more permanent location.

Inspire, Memorialize, Share

The Rotunda's designers had other, more lofty goals for this space as well. As expressed in extraordinary artworks, they sought to inspire future generations, memorialize key passages in the country's history, and share a collective respect for our common values. We'll look at five different spaces within the Rotunda to explore these goals further.

• The Apotheosis

The Apotheosis

Upon entering the Rotunda for the first time, visitors' eyes are immediately and involuntarily drawn up the very top of this room. There they will find a wholly unexpected fresco named The Apotheosis of Washington. (Fresco is a technique where paint is applied directly to wet plaster which draws the color in and locks it in place permanently. It's a difficult skill to master because the paint must be applied before the plaster dries, forcing the artist to work quickly on only one small section at a time.)

The Apotheosis (meaning the rising upward to heaven and being hailed there) is a grand allegory or symbolic story of the nation's founding and a tribute to George Washington. Often called The Father of His County, Washington, who served as Presiding Officer of the Constitutional Convention, Commander of the Continental Army, and the nation's first President, is shown seated in royal purple robes. On either side are women portraying victory and freedom. Completing the circle are 13 other women, each of whom represents one of the 13 original states. Surrounding this grouping are Roman gods and goddesses depicting War, Science, Marine, Commerce, Mechanics, and Agriculture –all key to the country's initial success. Some of the figures, all painted by Constantino Brumidi (remember him?) are up to 15' tall, in order to be clearly seen from the floor far below.

• The Frieze

The Declaration of Independence from the Frieze

Brumidi (1805 – 1880) was an Italian immigrant who devoted 25 years of his life to painting The Capitol. In addition to The Apotheosis (which took 11 months to complete), he painted most of the Rotunda Frieze, countless walls and decorative spaces throughout The Capitol, and even two ceiling scenes in the White House. Two years after starting work at The Capitol, Brumidi became a U. S. citizen.

Directly beneath the Rotunda's row of tall windows is a band of historical scenes that appear to be carved from stone. In fact, they, too, are frescos painted by Brumidi and others, but this time using different technique (trope l'oeil) meant to fool the eye of the viewer into thinking that the figures are all three-dimensional.

Brumidi planned and sketched 16 scenes for the Frieze. The first was another allegory; America as a woman, standing between an Indian maiden and history. The last was to be the discovery of gold in California. Before his death, Brumidi completed only eight of the scenes, leaving Filippo Costaggini to complete the last eight. Unfortunately, Brumidi and Costaggini had miscalculated and with 16 panels completed there remained a gap of some 31 feet. Congress then authorized Allyn Cox (not Costaggini who had sought the commission) to paint three additional scenes showing the end of the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, and the Wright brothers mastering flight at Kitty Hawk. In all, it took 75 years to complete the Frieze.

• The Eight Paintings

General George Washington Resigning His Commission

Encircling the base of the Rotunda are eight, massive oil paintings, each 12 feet high by 18 feet wide and inset into the Rotunda walls. So iconic are these paintings that you may well have seen one or more in your history books. The paintings were done on canvas which was then adhered to the curved Rotunda walls and surrounded by decorative frames.

The artist John Trumbull (1756 – 1843) was commissioned to paint four scenes from the nation's founding: The Signing of The Declaration of Independence, The Surrender of General Burgoyne, The Surrender of Lord Cornwallis, andGeneral George Washington Resigning His Commission. Though Trumbull imagined the poses, he took great care to depict each individual in the scenes, all of whom can be identified by name. Painted years after the events, each of these scenes is idealized and structured to be easily understood by the viewer. Trumbull's masterworks have become iconic representations of our history.

Though Trumbull had hoped to paint the remaining four pictures, they were instead commissioned from four other artists: The Discovery of the Mississippi by William H. Powell, The Landing of Columbus by John Vanderlyn, The Embarkation of the Pilgrims by Robert Weir, and The Baptism of Pocahontas by John Chapman.

Surrounding all eight paintings are stunning gold frames, the vertical sides of which are fasces, Roman symbols of multiple rods lashed together to form a stronger whole; an apt metaphor of strength coming from unity, just as the 13 states found strength in federation.

• The Statues

Portrait Monument to Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony

Interspersed among the paintings are nine statues (donated by the states) and two busts. Eight of the statues represent American presidents (Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, Jackson, Garfield, Eisenhower, Ford, and Reagan) while the ninth is of Alexander Hamilton, who served as the nation's first Secretary of the Treasury. (Notice that Washington rests his left arm upon a face.) One of the busts is of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., commissioned by Congress, while the other shows suffragettes Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony. The carving of this last is deliberately unfinished, suggesting the work remaining for full recognition of women.

William Penn’s Treaty With The Indians

• Sandstone Carvings

Above the paintings and below the Frieze are several bas-relief stone carvings. Four show silhouette poses of early explorers John Cabot, Christopher Columbus, Sir Walter Raleigh, and Sieur de La Salle. Two square carvings illustrate The Preservation of Captain John Smith by Pocahontas, and The Landing of the Pilgrims. Two additional, rectangular carvings show scenes of war and peace: The Conflict of Daniel Boone and the Indians and William Penn's Treaty with the Indians. And unlike The Apotheosis and the Frieze, all of these four actually are three-dimensional.

Did You Know?

1. George Washington's likeness appears seven times in the Rotunda, more than any other person: once in the Frieze, as a statue, four times in Trumbull's paintings, and once in the ceiling Apotheosis. Can you find them all? Jefferson is second, appearing once in the Frieze, once as a statue, and twice in paintings.

2. The volume of the Rotunda is roughly 1.3 million cubic feet. That means it could hold the water from nearly 15 Olympic size pools or more than 2.6 million basketballs.

3. On the other side of the Rotunda, there is enough space between the inner wall and the outer wall of the Dome to hold electrical and ventilation equipment, as well as a 300+ step walkway leading all the way up and out to the base of the Freedom statue.

4. The sandstone walls, from the floor up to the Frieze, were originally painted white, thereby hiding the variations in stone color and the rusty-looking streaks. After a 1905 restoration, however, it was decided to leave the stones unpainted. Do you agree?

5. After his design was rejected, Filippo Costaggini painted his angry face into the Frieze at the base of the tree that stands between The Death of Tecumseh and The American Army Entering the City of Mexico.

6. In addition to his work in the Rotunda, Brumidi decorated Capitol corridors with American historical scenes, but he left several spaces blank and unfinished, believing that America would have many more accomplishments in the years to come. One of those spaces has now been filled with a painting of Americans standing on the Moon.

7. At first blush, Trumbull's painting of George Washington Resigning His Commission might seem an odd or insignificant subject for a Rotunda painting, but it was in fact yet one more symbolic representation; this one indicting that the government is based on civilian and not military rule.

Chapter 5

National Statuary Hall

Welcome to National Statuary Hall

National Statuary Hall, included in all Capitol tours, is a truly remarkable space with an equally remarkable history. Seen today, it is perhaps the brightest and most inviting room in The Capitol. There you will find 35 statues, part of a much larger collection, each with an intriguing story.

In 1864, Congress gave the hall its present name and invited each state "…to provide and furnish statues, in marble or bronze, not exceeding two in number for each State, of deceased persons who have been citizens thereof, and illustrious for their historic renown or for distinguished civic or military services such as each State may deem to be worthy of this national commemoration…" And after much debate and some compromise, in 2012 Washington, DC was invited to contribute one statue –but only to the Congressional joint art collection, not the Statuary Hall collection. The District had hoped to place two statues in The Capitol and commissioned works depicting Frederick Douglas and Pierre L'Enfant. Douglas's statue now resides at The Capitol Visitor Center; L'Enfant's waits a half-mile away in the lobby of an official District office building at One Judiciary Square.

Among the collection, you'll find statues of five Presidents: Washington, Jackson, Garfield, Eisenhower, Ford, and Reagan.

Placing all 100 statues in Statuary Hall would have severely crowded the space and made it difficult to appreciate these works of art. In addition, the collected weight of all that marble and bronze might exceed the capacity of the Hall's floor. As a consequence, the remaining 65 statues can be found displayed throughout The Capitol, in the Crypt, the Hall of Columns, and elsewhere, including The Capitol Visitor Center. From time to time, at the direction of Congress, the statues are moved to different locations. The last rearrangement took place in 2008.

History

The House of Representatives by Samuel F. B. Morse, 1822

Like many other spaces in The Capitol, the Hall's appearance and use have changed over time. Accidental fires, purpose-lit fires by the British during the War of 1812, replacement of deteriorating materials, evolving architectural styles and preferences, and an ever-growing number of members of Congress have all been forces driving reuse and renovation. Since arriving in Washington in 1800, the House had been meeting in a room originally intended to House the Library of Congress. For a number of reasons, only the Senate or north wing of The Capitol was habitable by the turn of the century and while the Senate was able to convene in its own chamber, the House had to make do.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe was invited by President Jefferson to design the House or south wing of The Capitol. Both classically trained and educated in the classics, Latrobe took much of his inspiration for the new Capitol from his earlier travels to Paris and Italy as well as his work in London. His neoclassical style fit well with Jefferson's tastes; the President prized his copy of Palladio's Four Books on Architecture. Not surprisingly then, Latrobe's design for the House chamber (later Statuary Hall) was a grand, classical statement. Two stories tall, with a coffered ceiling and stately columns, it took its elliptical shape from Roman amphitheaters. It had very roughly the appearance of a quarter of a sphere. As stunning as this was, it was soon apparent that the elliptical shape, while well-suited to projecting actors' voices outward to an audience also made those same voices echo incomprehensibly on the "stage" itself. (Years later, when the echoes persisted, then Architect of The Capitol William Thornton suggested woolen cloth, dipped in arsenic to discourage moths, be hung across the fronts of the chamber's galleries.)

By 1807 the House's chamber was finally ready and the body moved from the library to the Hall, where they stayed until 1857, except for a five-year period when it was being repaired and rebuilt following the intentional burning by the British.

The Hall as we see it today was restored to its 1823 appearance in time for the 1976 Bi-Centennial celebrations. To appreciate what it must have looked like when in use by the House, we have an 1822 painting called Night Session in the House by Samuel F. B. Morse, the very same Morse who invented Morse Code and demonstrated his telegraph machine by sending a message from The Capitol Rotunda to Baltimore 22 years later. The painting, which today hangs just down the Mall in the National Gallery, shows Members desks arranged in semicircles around the Speaker's dais, an elaborate chandelier being lit to illuminate the room, and yards of red drapery hung all along the curved back wall.

Key Features

In the Hall are two spots (the foci of an ellipse) where sound plays a funny trick. Stand at one of these points and whisper. You will clearly be heard by anyone standing at the opposite point, no matter the noise and conversations taking place everywhere else. It's a favorite Washington myth that when he served in the House, John Adams would position his desk above one spot and pretend to fall asleep while all the while eavesdropping on members of the other party huddled over the other spot discussing their tactics. Part of what makes the whispering trick work today is the shape of the ceiling, which was much changed in Adams' day.

Throughout the room you'll find small, square, brass floor markers indicating the locations of the desks of House members who later became president. Markers can be found for Abraham Lincoln, John Quincy Adams, James Buchanan, Millard Fillmore, Andrew Johnson, Franklin Pierce, James Polk, and John Tyler.

Artwork

In addition to the Hall's statues, the artwork that garners the most attention is the marble carving set directly above the doorway opposite to where the Speaker would have sat. It's called The Car of History and was sketched and commissioned by Latrobe. It shows Clio, the muse of history (one of the nine muses) standing in a chariot rolling over signs of the Zodiac emblazoned on a globe, signifying the passage of time. George Washington's profile can be seen on the chariot as well as an angel blowing a horn to trumpet his fame. Clio gazes into the chamber and in her left arm rests an open book in which she appears to be recording to House proceeding for history. On the side of the chariot is a large clock, still wound from behind every Monday, to impress the members of the passage of time. On the opposite wall, in the niche and directly above where the Speaker would have sat, is the plaster statue called Liberty and The Eagle. In her outstretched right hand she holds The Constitution, guarded by the eagle. To her left is a snake, signifying wisdom, wrapped around fasces, representing the United States. A similar snake-and-fasces motif is found on the silver inkwell, in the present House chamber, on the Speaker's desk.

The Car of History Clock

Other Uses

Every four years the Hall plays host to the Inaugural Luncheon. After the swearing-in ceremonies and the departures of the former President and Vice President, the newly-elected President and Vice President, their families, Congressional leaders, and members of the Joint Congressional Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies adjourn to the Hall for a lunch and additional ceremonies. While similar Inaugural Luncheons have been held elsewhere, the tradition of using Statuary Hall began in 1981 with the inauguration of Ronald Reagan.

Although his portrait hangs in the current House chamber, when Lafayette returned to America and addressed a joint session of Congress, he did so in the Old House Chamber. The new chamber had yet to be built at the time of his visit.

Four presidents were inaugurated in the Hall: James Madison, James Monroe, Andrew Jackson, and Millar Fillmore. A fifth, John Quincy Adams, was not only inaugurated here but was actually selected here by the House of Representatives in 1824, after neither he nor any of his four opponents received the necessary majority of electoral votes. After his presidency, Adams served in the House for 17 years and in 1848 suffered a stroke while seated at his desk in the Old House Chamber. He was moved to the Rotunda and then the Speaker's rooms, where he died two days later.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg lying in state

Did You Know?

1. Other members of House who later became President, but did not serve their tenure in what is now Statuary Hall, were: George H. W. Bush, Gerald Ford, Richard Nixon, Lyndon Johnson, John Kennedy, William McKinley, James Garfield, and Rutherford B. Hayes. William Henry Harrison served in the House during that time (1816-1819) and later became President, but that was when the Hall was being rebuilt after the war. Andrew Jackson and James Madison served in House before the House was in Statuary Hall. John Quincy Adams served in the House after having been President.

2. In Morse's painting sharp-eyed observers can find the Car of History, Morse's father, and Pawnee Indian chief Petalasharo.

3. Clio, the Muse of History in the Car of History, was modeled on the sculptor's daughter. And if you look closely; you'll see there is actually no pen or quill in her writing hand and no words on the book's pages.

4. Though the room presents a harmonious appearance, it's materials came from many sources. The columns of Breccia marble came from along the Potomac River, but the columns' white capitals were carved from stone brought from Carrera, Italy. The black floor tiles came from Philadelphia while the white tiles were sawed from a block of Italian marble left over from the recent Capitol extension project.

5. Since 2000, states have been permitted to replace statues previously donated to the Collection. To date, there have been 13 statue exchanges, with three more pending.

Chapter 6

The Senate Chamber

Welcome to the Senate Chamber

Just like the House of Representatives, the U.S. Senate conducted business for its first 11 years at locations outside Washington, DC. From March 4, 1789, through September 29, 1789, and later from January 4, 1790, through August 12, 1790, both Houses met at Federal Hall in New York City. Then from January 4, 1790, through August 12, 1790, the Senate and House were located at Congress Hall in Philadelphia, next door to Independence Hall where The Declaration and The Constitution were adopted. There the House met on the first floor, the Senate on the second. Both chambers have been restored to their appearance in 1796, and 28 of the 32 desks in the Senate chamber are originals from that time.

The First Two Senate Chambers in The Capitol

When the seat of government moved to Washington, DC in 1800, the Senate occupied the space in The Capitol now known as the Old Senate Chamber. This two-story, semi-elliptical room is smaller but similar in design to National Statuary Hall on the other side of the Rotunda. But as early as 1805, plaster was falling from the wooden-lathed ceiling and cracks appeared in the wooden columns ringing the chamber.

Benjamin Latrobe, who had been appointed The Capitol's architect by President Jefferson, was charged with completing the south or House wing of The Capitol. While pursuing this work, Latrobe soon discovered the extent of deterioration in the north wing, including rotting floorboards and supporting timbers, as well as the precarious ceiling. Latrobe drew up plans that not only restored the north wing to safe use but radically transformed it as well. Insisting on using the best materials available and replacing wood with stone, his plan was, in effect, to move the entire Senate chamber up one floor so it would occupy the 2nd and 3rd floors of the building (to then be on a par with the new House chamber) and to transform the 1st floor space into a chamber for the Supreme Court.

To realize his design without tearing down the outer, stone walls of the north wing, Latrobe ingeniously designed what was effectively a building within a building. His new interior columns supported the two new chambers without transferring any of the load to the existing walls.

But the year1808 saw a serious setback. Latrobe had appointed John Lenthall "Clerk of the Works," essentially the construction foreman. Lenthall substituted his own design for the arches supporting the ceiling of the new Supreme Court space with tragic result. Upon removing the bracing beneath those new vaults, the ceiling collapsed. All of the workers except Lenthall escaped, whose body was recovered days later. Remarkably, the Senate chamber above remained intact and the Supreme Court's ceiling was soon rebuilt per Latrobe's original design.

In 1810 both the Senate and the Court occupied their new chambers, where both would remain until 1859. After the British set it afire on August 24, 1914, The Capitol lay in ruins and was unsuitable for use by either the House or the Senate. For the remainder of the year, Congress met at Blodgett's Hotel nearby, moving from 1815-1919 to a Latrobe-designed annex to Long's Tavern. This temporary site became known as The Brick Capitol.

Even before the war, Latrobe had been told how cramped the Senate chamber had become, due to the growing number of states admitted to the union and therefore growing number of Senators. So he then took advantage of the necessary rebuilding to enlarge the chamber, outfit it more grandly, and provide more space in viewing galleries. Central to Latrobe's plans were a number of full- and half-height marble columns and study, brick vaults finished in plaster overarching both chambers. The columns were procured from marble veins in nearby Maryland, but the process of removing the stone, transporting it to The Capitol, and carving and polishing it on site was beset by delays and difficulties that would eventually outlast Latrobe's tenure as The Capitol's architect. And Latrobe's brick vaulting was rejected in favor of timber, which would be cheaper and hasten the completion of the rooms.

By his own admission, Latrobe was not always the easiest person with whom to get along, and by 1817 the combination of his temperament and a number of events joined to push him to the edge. He had just received word of his son's untimely death, was in danger of insolvency, was still smarting over President Monroe's direction to use timber vaults, and was constantly opposed by those who wanted to change his plans without the knowledge to understand them. His pride got the better of him and he exploded in an angry outburst against the Commissioner overseeing his work, all in the presence of the President. He resigned that very day.

When the columns were finally installed and the two chambers completed and restored, it was under the eye of the new architect, Charles Bulfinch of Boston. Bulfinch thought Latrobe's design was too constrained, and in an effort to add more elegance to the chambers, outfitted them with crimson drapery and brass lighting fixture. The rooms as they looked then are much like we see them today.

Old Senate Chamber

In 1976, celebrating the nation's Bi-Centennial, the Senate chamber was restored to its 1850s appearance and is today referred to as the Old Senate Chamber. The room is open to the public but on rare occasions is reserved for the Senate when they require a space in which to meet that affords a more collegial and less formal atmosphere. When the Senate moved to its present chamber, the Supreme Court moved upstairs to the Senate's old quarters and remained there until 1935, when a separate Supreme Court building was completed, east of The Capitol. The Court's first floor room has also been restored (to its 1854 appearance), and it, too, is open to the public.

The Current Chamber

On January 4, 1859, the Senate met for one last time in its old chamber and then ceremonially walked into its new chamber. The new space was rectangular, though at one point it had been proposed to model it on the room now known as Statuary Hall, bringing with it the persistent problem of poor acoustics. And it was windowless, a condition many Senators would publicly regret over the coming years until air conditioning was introduced in 1920. The room also had a glass roof, richly and allegorically decorated. An inspection in 1938 determined that the roof had become structurally unsound and at the end of the session in 1940, the Senate moved temporarily back into its old chamber. Because the war was still being prosecuted, the Senate opted at that time to simply reinforce the ceiling with a truss work of steel beams. In 1949 the chamber was roofed over, preventing falling rain from hitting the glass and making it impossible to hear. The ceiling was replaced and is now artificially lit. In 1950 the rest of the chamber was remodeled.

The remodeling served as an opportunity to change the appearance of the room, making it less Victorian, more modern and spare. The wooden rostrum, however, was replaced with a marble one, the exact opposite of what the House had done earlier.

There are no paintings or portraits in the chamber, unlike those that flank the Speaker's chair in the House. But, as the Vice President serves as the President of the Senate, the gallery above is ringed with 20 busts of past Vice Presidents; 26 others are displayed throughout the Senate wing. Each of these Vice Presidents served as Presidents of the Senate.

Senate Desks

Mahogany Senate Desk

Unlike the House, each Senator is assigned one of the desks in the chamber and these hold great importance to the members and historical significance to the institution. Of the 100 mahogany desks and chairs in the chamber today, 64 were brought in 1859 from the old chamber and are still in use today. Those include the prized desks of Daniel Webster and Jefferson Davis. In one tradition that seems at odds with the formality and ornamentation of The Capitol, Senators use penknives to carve their names inside the desk drawers. This practice arose sometime around 1900 and continues today. The feet on either side of the desks are wrapped in vented, metal sheathing, a reminder of an earlier and quite elaborate heating and cooling system that pushed air up from below the Senate floor. At one point air was actually blown across large blocks of ice and then sent up into the chamber during hot summer months. And about that persistent acoustics problem, each desk is now discretely fitted with a small speaker and microphone, making sure every Senator can be heard by his or her colleagues.

Did You Know?

1. Beginning sometime in the early 1800s the Senate kept an urn of snuff on the Vice President's desk. The custom at the time was to take a small pinch of snuff (powdered tobacco) and rapidly inhale it through the nose. In 1849/1850 the urn was replaced by two small, Japanese, lacquered boxes. Today those same boxes are affixed to either side of the Senate's rostrum, and in a nod to tradition, they are still kept filled with snuff.

2. Imagine not being able to use a cell phone, tablet, and laptop at your place of work. None of these devices are allowed on the Senate floor. Such a ban, it is hoped, will preserve decorum and encourage Senators to engage more directly with each other.

3. While the chamber is elegantly designed and decorated throughout, it is somewhat surprising to see that the Senate's gavel is small, fairly plain, and looks nothing like the hammer-style gavel of the House of Representatives. Used to open and close sessions and call the members to order, the gavel is an hour-glass shaped piece of carved ivory, just over two and a half inches tall. It was a 1954 gift from the government of India, replacing a broken original.

4. Congress, in a Joint Session, actually returned to Federal Hall for one day on September 6, 2002, as a show of support for New York City, one year after the 9/11Trade Center attacks.

5. The curved outer wall of National Statuary Hall is elliptical, whose two foci are the locations of the whispering spots. Though the Old Senate Chamber is semi-elliptical, it, too, has foci that mark its own, little known, whispering spots.

6. Busts of the vice presidents are commissioned after their tenure of service. Still to be sculpted and placed in the Senate wing are busts of Joe Biden (2009-2017), Mike Pence (2017-2021), and Kamala Harris (2021-2025.

Chapter 7

The House Chamber

Welcome to the House Chamber

So central is it to our representative democracy, that establishing the U.S. House of Representatives, one of two bodies in the Congress, was the very first task of The Constitution. And in line with its closer association with the country's citizens, the Founders provided that "All bills for raising Revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives…" If money was to be spent, then that act should be supported by the people. With that exception and concurring in treaties and confirming presidential nominees, in all other respects the House and Senate are equal partners of the legislative branch of our government.

Evolution of a Meeting Space

While meeting in New York City, the temporary capital of the new nation, Congress passed the Residence Act, establishing a permanent capital and requiring that a Capitol building be completed and ready for Congress to occupy by December 1, 1800. However, due to an inability to secure materials and cost overruns, it was decided to put all effort into completion of just the north wing (now the Senate wing). Into that portion of The Capitol, probably less than a quarter of the full Capitol's present size, moved the House, Senate, Supreme Court, and Library of Congress on November 17, 1800. One month later, on December 16, the House convened its first session in the new Capitol, its 106 members meeting in the library.

By the next year, a temporary structure was erected for the House, located to the south of the main building and connected to it by a wooden walkway. It was octagonal in shape, reminding some of a Dutch oven. And for that reason and its poor ventilation, it was soon dubbed ‘The Oven.’ In 1804, the oven was torn down to make way for architect Benjamin Latrobe's newly-designed south wing, with the House retuning to the library for its meetings, where it had to accommodate 36 additional members since last occupying that space.

Temporary House Chamber ("The Oven"), on the left

By 1807 the south wing was complete and on October 26 of that year the House convened in its new quarters. The chamber was located in what we today know as Statuary Hall. Though praised for its beauty, it had two major drawbacks; it was exceedingly difficult for members to hear the debates taking place among them, and the multiple skylights often made the space exceedingly bright. Latrobe dampened echoes by hanging drapery nearly 20 feet long between the columns. The matter of lighting would be addressed later. One of the casualties of the War of 1812 was The Capitol itself. The British had been intent and methodical in their attempts to burn the building down. In the House chamber they shot missiles up through the skylights, hoping that falling sparks and embers would ignite the roof. When it did not, soldiers were sent up to the roof, reporting that in fact it was not made of wood, but instead sheathed in metal. Frustrated, the British then piled all of the furnishings together, smeared them with gunpowder paste, and lit them afire. The damage was devastating; the heat of the fire was so intense that the skylight glass actually melted. After several years meeting in the Brick Capitol, a cramped building across the street, the House returned to a restored chamber, which, unfortunately, still suffered from poor acoustics.

By 1857 the House moved into its new chamber, located where we see it today. By 1864, the then-abandoned old House chamber was designated National Statuary Hall. A new floor was laid and a new ceiling built, turning the space into something close to what we see today.

Nearly 90 years passed without major renovations to the chamber until it was discovered that the aging space had serious structural problems. Throughout the 1940s and especially during WW-II, it was thought imprudent to spend extraordinary sums on rebuilding the chamber, so instead large steel I-beams were raised around the walls, supporting a lattice of beams holding up the ceiling.

During 1949-1950, the House decamped temporarily to the Ways and Means committee room in the Longworth House Office Building, while repairs and redecoration brought the Representatives' hall close to its present condition.

Musical Chairs – And Desks

The desks and chairs used by members of the House over the years reveal much about the growth and changing aesthetic of the country.

Klipper desk, 1873

From the start, members of the House had assigned desks, much like the Senate does today. But the size of the two chambers, relative to the number of members in each, clearly argued for a change in the seating. Today the House chamber is roughly a quarter larger than the Senate (12,927 square feet vs. 9,040 square feet) but has more than four times as many members. Despite their elaborate appearance and symbolic carvings, the House desks were more than just ceremonial pieces; they were intended for actual work, containing a drawer, a shelf, and in some cases, an inkwell. Until the opening of the Cannon House Office Building in 1908, the desks were quite literally the offices of the Representatives.

One of the reasons for changing quarters so often was to accommodate the growing number or Representatives, due both to the continuing increase in the number of states and a similar increase in the U.S. population. When the House first convened, in 1789, there were 60 members and a total population of fewer than 4 million. The number of Representatives continued to grow until 1913 when it hit 435, where it is today. In 1959, when both the states of Alaska and Hawaii were admitted to the Union, the number was increased to 437, though it later returned to 435 in 1963.

Today, there is actually some room for growth; the House chamber itself now has 448 bench seats. Six of those additional 13 seats are occupied by non-voting members representing the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

And it's interesting to note that the one and only time George Washington publicly expressed an opinion during the Constitutional Convention was to suggest that the ideal ratio for the House would be one member for every 30,000 persons. If that rule of thumb were followed today, the House would have some 11,163 members, more than 25 times its current size and clearly an unmanageable number for debates and persuasive discourse. Conversely, each Representative today, on average, has roughly 770,000 constituents.

Between 1857-1873, there were 262 oak desks and chairs, between1873-1901 the House had 304 smaller and less ornate oak desks, between 1901-1950 even smaller desks were placed side-to-side, forming consecutive arcs around the well. And since then, desks have vanished, replaced by bench-style seating with armrests separating each occupant. Owing to its larger size and bench rather than desk seating, the House chamber is used for Joint Sessions of Congress, including State of the Union addresses. But even then, extra chairs have to be brought in to accommodate members of the Supreme Court, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the president's cabinet, the diplomatic corps, and more. At these moments it truly is a full House.

Inside the Chamber

As in the Senate, and throughout The Capitol, the House chamber contains a number of objects of singular beauty and symbolic importance.

The Mace

• The Mace